The essay is often the go-to assignment in humanities courses, and rightfully so. Especially in the text-based disciplines, the craft of the essay is highly valued as part of practicing the work of the field. More broadly, developing effective writing skills is a universal learning objective in higher education and, to varying degrees, is often dependent on these humanities classes. There are, however, alternative assignments in which students can rigorously but creatively perform their understandings in summative projects to be rigorously assessed, while still practicing–and even calling attention to–the habits of mind of the discipline.

Students synthesize and unify multiple themes or concepts through metaphors, and then explicate their own thinking

This assignment encourages students to practice and perform a variety of ways of thinking:

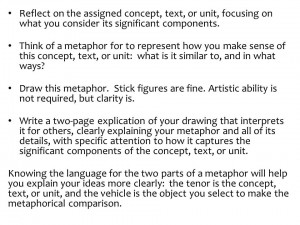

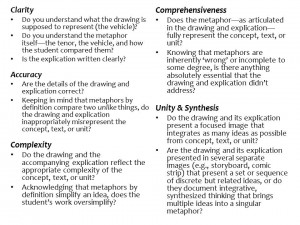

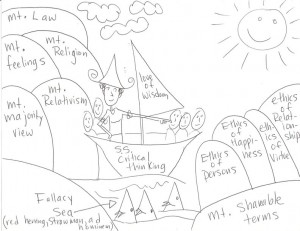

It involves two parts: first, students draw an image of a single metaphor they use to make sense of a concept, text, or unit (or several), and then–more importantly–they explicate their drawing. Sample instructions are in the box to the right.

Ultimately, metaphor maps are less about the drawing and more about how students synthesize and unify complex, multidimensional thinking around a single metaphor–and how clearly and effectively they explain these ideas. This strategy stretches them beyond the typical modes of learning and challenges them to organize their thoughts in a new way.

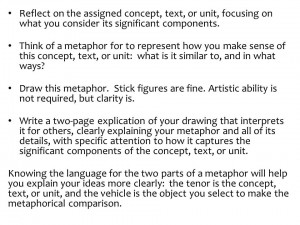

Some suggested criteria for assessing metaphor maps include the following:

Each is further developed in the box to the right.

Examples

Students perform the work of editors or curators

A significant genre in the humanities is the anthology, collections of poems, stories, essays, artwork, etc, selected, researched, and annotated by an editor. Students can take on this role of editor, acting as curator and commentator as they establish a sense of authority and ownership over the material (Chick, 2002). They make intentional decisions about which pieces to include, what contexts to provide in their editorial notes, and even what paper, binding, font, and illustrations to use. If the pieces are short enough, as in a poetry anthology, students can be required to write or type the pieces themselves “to engage with every letter, every punctuation mark, every capital or lower-case letter, and every line break, and to consider the meanings of these choices by the poet” (p. 420). They include a title page, table of contents, prologue, and epilogue framing their anthology.

Giving students guidance for their editorial responses to each selection is helpful. Some possibilities include the following:

Ultimately, students are “defining their own aesthetics” and becoming “aware of the ramifications of making aesthetic choices” by creating their anthologies (p. 422). This analysis can then be connected to the formation of the canon, revealing the subjective nature of “what they may have thought were universal or unquestioned notions” of quality and significance in the field.

Resource

Students visually showcase their learning and present it to wider audiences

Le e Shulman, President Emeritus of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, has written of the importance of engaging with our teaching as we do our research–as “‘community property”: “We close the classroom doors and experience pedagogical solitude, whereas in our life as scholars, we are members of active communities: communities of conversation, communities of evaluation, communities in which we gather with others in our invisible colleges to exchange our findings, our methods, and our excuses” (2004, p. 140). What if we asked our students to do the same with their learning–as fellow citizens of the university, emerging scholars and researchers and producers of their own knowledge? In this model of making learning community property, the audience for student learning extends beyond the instructor and often even classmates–reaching out to a larger community that remains authentic to disciplinary and learning goals.

The genre of the academic poster is a staple in the natural and social sciences, displayed at conferences and other meetings to share research findings with peers, and students in these fields begin practicing these ways of going public fairly early. As Hess, Tosney, and Liegel demonstrate in “Creating Effective Poster Presentations” (2013), these visual representations of knowledge “operate on multiple levels”: “source of information, conversation starter, advertisement of your work, and summary of your work.” Poster sessions can be lively sites of conversations about new and interesting work in the field, but few (if any) disciplines in the humanities use this genre. In this way, assigning posters may feel inauthentic; however, the genre’s attention to sharing content in a concise, visual, and public format can be adapted to more closely reflect the meaning-making in the humanities. In fact, given many humanities disciplines’ appreciation of form reflecting content, the poster can make visible specific rhetorical moves, encouraging students to think not only about their ideas but also how they form their ideas.

It’s important to note that the poster is a conversation starter: it doesn’t have to present the project in its entirety. Instead, it can highlight part of the project, which the presenter uses to begin an oral explanation of the rest of the project.